Barry Kelly Interview

Mack Garrison and Barry Kelly talk a little shop in this interview with the Emmy award-winning artist and director at Titmouse, who shares his journey in the animation industry. From his early influences and experiences growing up in Nebraska to his work on major projects like Star Wars and Star Trek, Barry discusses the evolution of animation, the tools and techniques used in the industry, and the importance of storytelling. He reflects on his inspirations, the challenges of the animation process, and the significance of creating content that resonates with both his younger and older selves.

Takeaways

Barry Kelly describes himself as a 'nerd from Nebraska' who found his passion in animation.

He emphasizes the importance of being of service through entertainment and creativity.

Barry's journey into animation was influenced by his love for comics and cartoons.

He highlights the cultural impact of shows like The Simpsons on generations of viewers.

Working on Star Wars allowed Barry to channel the feelings those movies gave him as a child.

The animation industry is driven by people and collaboration, not just rules and guidelines.

Barry discusses the challenges of getting mature animated content accepted in the U.S. market.

He reflects on the importance of flexibility in animation tools and techniques.

Barry draws inspiration from comic book artists and filmmakers like Paul Verhoeven and Ridley Scott.

He believes in the importance of making content that resonates with both his eight-year-old and eighty-year-old selves.

Chapters

00:00 Introduction to Barry Kelly and His Journey

02:56 The Impact of Animation on Personal Identity

05:58 Working on Iconic Franchises: Star Wars and Beyond

08:53 Navigating the Animation Industry: From Nebraska to LA

11:58 Early Career Experiences and Learning Opportunities

15:11 The Evolution of Animation Tools and Techniques

18:03 Flexibility in Animation Production: Tools and Techniques

18:59 The Evolution of Animation Tools

20:48 Experiences at Titmouse Animation Studio

22:06 Dramatic Storytelling in Animation

25:03 Memorable Projects and Personal Highlights

27:10 Balancing Artistic Integrity and Industry Demands

29:03 Quality Assurance in Animation Production

33:05 Inspirations and Influences in Animation

36:52 New Chapter

Transcript:

Mack Garrison (00:00)

Hey, what's up everyone? Mack Garrison here, co-founder of Dash Studio, and I'm excited to be back with another speaker series interview. And we got the talented Barry Kelly, who's a nerd from Nebraska, self-described nerd, who also loves to be an Emmy award-winning, who happens to be an Emmy award-winning artist working in animation for the past 18 years. Director at Titmouse cartoons, his credits include Star Wars, Galaxy of Adventures, Son of Zorn.

and Venture Bros. He recently wrapped up the fifth season of the hit sci-fi series Star Trek Lower Decks for CBS Paramount Plus. Welcome to the show, Barry. So glad to have you here.

Barry (00:34)

Hey, thanks for having me, Mack Morning on this side.

Mack Garrison (00:36)

feel like,

my gosh, that's right. You're up bright and early. I'm on my third cup of coffee. So if that comes through in the interview, you know why. I think it's first, we need to just like acknowledge like how cool our lives are right now. Cause we're sitting here, you're coming to speak at the Dash Bash Animation Conference and we're gonna talk shop and just kind of hang out like pretty neat that this is our job in middle of the day for me at least on a Tuesday.

Barry (00:45)

Yeah.

Yeah,

I I'm always like, am I, am I doing, am I useful or I don't know how to do anything else. You know, like, I don't know, like I know how to draw pictures and I know how to, you know, make like like a, like a cool image. And I'm like, I'm so into like comics and toys and all these things. And I'm like, I hope, I hope I can entertain somebody so I'm useful, you know, that being of service is something I subscribe to, you know.

Mack Garrison (01:21)

I saw the news come out recently that 2024 YR4 asteroid that could hit us. don't know if you saw this in like 10 years. was a random, yeah, there's a random asteroid and it's plummeting towards us. I think there's like a one in 42 chance that it hits us. And I was thinking, I was like, you know, if there was like a shelter, know, Greenland style like shelter or something like that, we would not make it. Like they are not looking for animators to join the team. Maybe if we were architects or someone in

Barry (01:27)

No, no, I'm assuming it's happening all the time. This is what I assume.

Mack Garrison (01:49)

you know, healthcare space.

Barry (01:50)

Or in those scenarios,

I always think like, you know, you have to do a tally of like, what can you do? What can you do? What can you do? And like, I can build lodging, can build, I can hunt, I can do this. And then it gets to me and it's like, I can draw and they're just like, your food. And they're just gonna, you know, I'll just be the thrown in the fridge.

Mack Garrison (01:56)

Right.

You're like I can make a good joke from time to time on occasion

Barry (02:09)

Yeah, yeah, on occasion. It's

quantity over quality though.

Mack Garrison (02:14)

So funny, it feels so accurate. But yeah, no, you're right though. I mean, we are in a cool space. It is lucky to be able to do what we do. I'm always curious how folks end up here because like animation has a multitude of different routes from like more of the entertainment space, production space. mean, there's a lot. When did that moment kind of hit you where you were like, oh, animation's kind of like the direction I need to go?

Barry (02:37)

I always feel like there's like a group of wannabe comic book artists that got sucked up by the animation industry and I'm definitely one of those. There are comic book artists that were legitimate that actually got published for real that became sucked in the animation industry but I'm definitely one of the ones that's like I can draw kind of. I like film, you know, I like all these things and like you know when I moved out to LA it was kind of like my talents that I could you know that I was okay at.

Mack Garrison (02:56)

Mm-mm.

Barry (03:06)

which was kind of drawing, kind of film stuff, kind of like led me to like the combination of the two, which is animation. And I don't know why I always think that, like, I never thought I'd get animation, because I've loved cartoons just as much as I loved anything else. Like, Simpsons and Batman were huge in my life. And think Simpsons kind of like probably has like a huge effect on more people than we realize, just because it's been on for so long. There's generations now. Yeah, there's just like...

Mack Garrison (03:21)

Mm.

my gosh, my childhood. Yeah, it was like

after dinner it was like Simpsons were on, you know, my household.

Barry (03:33)

Yeah, it's like reruns.

Yeah, reruns of the Simpsons was worth it. And like now like there's generations of kids who know a Simpsons I don't know, you know.

Mack Garrison (03:40)

yeah, which is really interesting in this new, not to talk too much about the marketing side of it, but like, you know, you have these like worlds, like, you know, Disney has a Simpson ride. There's the old Simpson shows, there's the characters and how all these people are coming into the world building from different areas. It's just kind of wild and bonkers this day and age.

Barry (03:44)

That's fun.

Yeah, I think that was something else that triggered my... I guess I'm trying to think what was a good example where you saw the movie of something, like maybe Transformers or something, and then you saw the toys and you're like, well, that's kind of different, but it's the same. And you kind of realize that there's like... When they become a different medium, it's almost like you get a different expansion of that IP or that idea. And it's really cool to see how it's translated.

Mack Garrison (04:08)

Mm-hmm.

Barry (04:26)

I think early on, like, wasn't ever like, there was no like definitive version of anything, like all the, all the like, uh, whatever came out kind of became your, you know, Oh, that's what they look like as action figures. That's what they look like is, is that it's like, is like that, that whole world that you're talking about, it kind of just adds to it.

Mack Garrison (04:36)

Right.

Was it,

were you growing up, were you a big Star Wars fan? I'm just thinking about, you you got to work on like Star Wars, Galaxy of Adventures, these kind of like little shorts, like how did growing up being a big fanboy of Star Wars kind of, Star Wars kind of translate into that.

Barry (04:45)

yeah.

Yeah.

I mean with

those shorts it's kind of like, there's a certain feeling that those movies gave you, gave me, and that's kind of what I was trying to channel. What's pretty special about, at least for me with those shorts, usually if you're making something of Star Wars today you have to expand on it or maybe go back in the prequel origins of Star Wars and what was fun is I got to just mess with the three characters that I...

love in Star Wars, which was Luke, Leia, Han, and Chewbacca, and Darth Vader and stuff. Not many people get to just play with those characters. what I got to do was make the way those feet, the feelings that those movies gave me, how important those fights or those confrontations felt. I got to do that and make those animations feel that way. I made them feel a little bit more epic or more dramatic than maybe they would.

watch the movie, a little bit, you know, they're shot with real people. And then this one, I get kind of get to do like, the excited animated, dramatic version that just capturing like how they felt to me as a kid. those are special.

Mack Garrison (05:58)

With something like that,

a brand that's like has so much history, right? For so many people, when you get on a project like that, I don't know exactly what the terminology would be, but like a character Bible, for lack of a better word, like are there things like you get that, you're like, all right, these are do's and don'ts, you can explore your take on it here, but you gotta be honoring this piece of it. Did you get a lot of that with that project?

Barry (06:20)

A

little bit, yeah. It's more the people that you're working with that kind of become that Bible. There was a guy named Mack Martin who is kind of like the Star Wars Bible in a way. But they all kind of know, they want you to know and don't know about what else is going on so that you don't step on anybody else's toes. It's very much people driven. the Lucasfilm, it's a story group that they call it. And they're all pretty great. they're all, no one is really like,

You can't do this or like you can't go too far like it's I was kind of surprised at how much like like I'm like Can I cut off someone's hand in this you know like they did it they did it in the movie? But can we do it and they're like yeah, well it happened so we can do it like it's like they're very much about like It what encapsulates Star Wars and other properties is like you know you need it to be dramatic when it's dramatic You need to be scary when it's scary you need it to be funny when it's funny and it's like as long as you're pushing those moments where they're supposed to be they're all important and I think like

Mack Garrison (07:00)

Yeah, right.

Barry (07:18)

Yeah, as far as like the Bibles and whatnot, they there's so much, like you said, there's so much history. There's so much 30. mean, at that point, there's 35 years of books and and and comics and everything. And there's definitely like it was after Disney. So there was definitely like a chunk of stuff that like is called legacy. And that's the stuff I grew up on. like they're still they're still trying to like, you know, they don't want to.

Mack Garrison (07:30)

Right, yeah.

Mmm, true.

Barry (07:45)

completely exercise it from the speed from they're kind of like we don't like like weaving it into some of the the the new Disney like post Disney canon and stuff. So there is like a little bit of that going on but they kind of the story group is kind of like the ones who kind of keep everything on track as best they can which sounds like a stressful task because I don't know how you please everybody when you're in that kind of like yeah.

Mack Garrison (07:54)

right, sure.

Yeah, a hundred percent. can't write. I mean, there's no

way you're just trying to massage it the best you can. That's so wild. Yeah. I was obsessed with star wars as a kid. I had like, one of my friends were like collecting baseball cards. had like the star wars customizable card game. Like I don't even know. Like I don't even people realize that that was a thing, you know, just investing tons of money into it. You know, it's like sitting in a drawer somewhere. Maybe it'll be valuable at some point.

Barry (08:10)

Mm-hmm. Mm-hmm.

yeah?

There

were tournaments, people played that, just like Pokemon, know, that was a big thing. And your friend group, yeah, you might be the only one.

Mack Garrison (08:31)

I know, but you're like one of five people who knows that that exists. Yeah, you're right.

All right. So tell me this, you you grew up in Nebraska. I wouldn't exactly say thriving animation scene, but I don't know, you know, Nebraska could be, ⁓ how did you end up making the move and saying like, cool, I'm gonna go out to LA or like, was it school and full sale that really sent you down that direction? Like, how'd you kind of go down that path and get out into the industry?

Barry (08:53)

I was, I always had some encouraging art teachers growing up. But what was kind of like the trigger for me was in high school, there was like kind of like a lottery grant to our school. Our school was pretty good. Like they had like some of the computer labs, like they had PCs and something that I think that was new to me. Like I was used to every school having Macs. So we did have PC labs and stuff. So like we could, we could mess around with Photoshop and stuff. Excuse me. But

Mack Garrison (09:11)

sure.

Barry (09:18)

One thing that happened in my senior, like junior year of high school was our school got like a lottery grant and they created like a technological school. they had, they had an art school. had like, cannot, like they called it a zoo school. It's like a science kind of magnet school, but they had this tech, this technology one and it had like three brand new computer labs. And like some of it was for like coding and learning like, um, Oh gosh, Cisco that stuff. And like, and then the other one was like,

Mack Garrison (09:31)

Nice.

⁓ sure, yeah, okay.

Barry (09:45)

I think they called it like creative or arts program or something like that. it's pretty much a computer lab that had like Photoshop, Final Cut, After Effects and Flash. This was like Macromedia Flash. This is Final Cut like two. Yeah, Like Photoshop was like six and like our teacher actually wrote the technical manual for Final Cut Pro, but like

Mack Garrison (09:54)

sick.

Yeah.

Yeah. Final Cut's like, we're glad to be open right now and working.

Barry (10:16)

It was generally kind of teachers who also didn't really know the software either so much. So it was, it was a lot of us just fucking like messing around and just screwing up like, like in, in, in the programs like crazy. And eventually like, I don't know how we wrangled ourselves to make some video projects, but we did that and kind of like learned, you know, in high school, like a very shitty pipeline of, you know, recording on high eight digitizing it, adding special effects to it and green screen chroma key stuff.

Mack Garrison (10:40)

nice.

Barry (10:45)

And it got us some like stupid awards that, you know, like we won like an iPod, like the first iPod, the very first iPod, which is still, which is still the best iPod I think I've ever had. It's like five gig. It like lasted, had the longest battery. It worked the best. Yeah. Yeah. So that was like our prize at the time, but that kind of like, kind of like gave me just some tools that I could, like I could work with now. Like, you know, you got the iPhone and you got, you know, the

Mack Garrison (10:51)

You got it, nice, 1. ⁓ my gosh, 100%.

The the scroll wheel, the tactile nature of it, 100%.

Barry (11:14)

Final Cut on the iMovie and all that stuff. yeah. Yeah, yeah, I can't believe it. Yeah, like all the face swapping and all the effects and stuff like, like, but that kind of gave me just like a good tactile knowledge of like how to use software and stuff and like what was universal between programs. And then after that, like it was like, okay, I literally saw Full Sail in the comic book.

Mack Garrison (11:16)

I mean, TikTok is probably more powerful than what we were learning Final Cut on the old days, right?

Yeah, crazy.

Hmm.

Barry (11:40)

Like they had put ads in comic books. Yeah. And I was like, well, this is everything I want to do. I'll just go there. And then that's literally how that was my decision maker. I was terrible in school. I was never going to go to like a fancy, you know, on education. That is true. That is 100 % true. I just remember that now.

Mack Garrison (11:41)

⁓ no way.

That's amazing.

School for you had to come out of a comic book.

That's so funny, I love that. You struck a memory for me. I'm jealous at least you had teachers who kind of knew what they were doing to kind of direct you in high school, at in the early days. My first animation experience, this is not even a joke, this is literally my first animation experience. It was PowerPoint that you could adjust. So in PowerPoint, you could adjust so the slide playback was like 0.1 second. So I'd made this huge PowerPoint deck and just flickered through the slides to get the image. I know, so credit to my teacher for coming up with that. It was a flip book.

Barry (12:17)

yeah.

That is so smart. That's a flipbook. That's so

smart. That's awesome. Wow.

Mack Garrison (12:25)

was a digital flipbook. That was the first introduction to animation. I was like,

this is kind of cool. Maybe I'll do some more of this stuff. Super funny. So you ended up at Full Sail and then graduate. And did you go directly like kind of into the entertainment space out there? Like intern, get a job, did you go freelance? Like how'd that kind of roll?

Barry (12:30)

That is awesome. Never thought of that.

Yeah, so I went to Full Sail for a year and me and my buddy graduated and a bunch of guys moved out to LA, got in house together, just invaded each other's space. And then, I mean, I didn't know what to do out there. You're just trying to make friends, know? It's hard to do that. But one of my first jobs, mean, some of the crappier gigs I had was like I was an extra in...

Mack Garrison (12:53)

Sure

Yeah.

How nice.

Barry (13:07)

in

the background of a few shows, was kind of funny. I could tell mom I was going to be in the show and she'd catch me in the background of like Joan of Arcadia or something back in the day. But that was still interesting. I went to Full Sail to learn cameras and productions. So was still kind of getting to just watch them make stuff, even when I was a boring background artist. And then I kind of did the same thing. I was almost like an extra in video game industry. I became a video game tester, which was just like

Mack Garrison (13:16)

Lazy.

Yeah.

⁓ wow.

Barry (13:37)

you an office job, unlike the worst office job, because it was like you're, you're just shoved in, you know, offices, cold, you know, hospital feeling.

Mack Garrison (13:46)

I have vision

of Grandma's Boy. When I think of video game testers, Grandma's Boy, that sounds like an amazing job. And it sounds like in an office park, basically.

Barry (13:49)

I wish. Yeah.

And I, yeah,

think, I think, I think that that job does exist, but it's like, it's like, well, I learned like, if you were a game tester, if you work for the publisher, you're like, it's like 500 to you just playing the game. They just need hours of the game. But if you're with the developer, you're getting to talk to them and the artists and also, and you're like, oh, that's like where like, if you were, if you could work at the developers, that's where like, if you're a video game.

wannabe talent and like when that's that's your pad like you want to work with those guys because then you're actually and the publishers is just kind of like you're the guy just reading the book you know just just reading everything making sure like spelling yeah you're just bodies for the for the for the grinder or whatever but but no i while that while that was going on i was trying to get better at drawing and i got into i got an internship with a place called animax and that was like flash at cartoons like like like like back in the day and it was like

Mack Garrison (14:17)

Mm-hmm.

I see.

Yeah, it makes sense, right?

wow, okay.

Barry (14:45)

They were technically probably a competitor to Titmouse. There was like four or five like flash studios that were pretty big out there and Animax is one of them. And I was just doing, I was a story intern drawing like really bad, like revisions to storyboards on paper to, for some like national geographic shorts, like little, just, it was all like, it was either like, like websites for Disney or like, you know, like

Mack Garrison (14:47)

Mm-hmm.

Barry (15:11)

medical cartoons to teach kids about asthma, like all that like kind of like medical stuff. But it was all like practical work, like I was editor, compositor, I learned like I couldn't really draw, so I couldn't really animate that well. So that was learning from like animators who could animate very well as learning from story artists who could draw pretty well. But I kind of became like the de facto like compositor editor guy for them, like because of that all that work that I learned in high school, so I was still doing the same thing.

Mack Garrison (15:13)

yeah.

Yeah,

well, essentially, it's kind of all came together as kind of this generalist, right? Being able to do all these different things for the shop, you probably got a lot of exposure and trying different stuff there too, which is cool.

Barry (15:46)

Yeah, yeah, yeah, no, like, I guess I felt like definitely that whole jack of all trades, master of none thing. Cause I was like, it was like what I, and I think, I think I wasn't sure if I was going to stick in animation just cause I wasn't doing the art side. And like, and also we weren't doing like super cinematic storytelling, which is what I wanted to do. And, ⁓ 2008 happened. That was like the housing boom and like people got laid off and you know, I was kind of like editing on freelance and all that stuff.

Mack Garrison (15:51)

Yeah, sure.

Right.

Yep.

Barry (16:12)

I'm still trying to draw and I but I just hunkered down I was like I gotta get good at drawing and I like took like two years of like workshops like sculpting drawing all that stuff

Mack Garrison (16:19)

Sure. Today

they made it through like, cause I mean, flash kind of had its heyday and then kind of dissolved, right? Like did, were they still around the navigating? Were you there when they were navigating flash basically?

Barry (16:24)

Yeah, yeah, yeah. I think

they are still technically around, but it was like, at the time, it was like everyone realized that like, I think everyone learned like, why are we making websites in Flash? Like, why would we do that? Like there's whatever Web 2.0 came out at the time, or HTML2, I don't remember. And I think a big thing with them was like, they were making...

Mack Garrison (16:38)

Yeah, right.

Barry (16:49)

Everyone wanted to make a virtual world like for their toy. Like if you bought a toy or whatever, you go on here and you can make your avatar and whatnot. you know, it's kind of, it's not too different from today, but like everyone was making them in flash. And I think that was really when they realized like, we don't need to make these in flash. Like you can make them in something else or something smaller.

Mack Garrison (16:51)

right.

Yeah.

I wrote.

Well, Flash was so insane.

I mean, I remember doing Flash, learning it myself, and I'd open up the program for stuff that I worked on all day yesterday, and it was just gone. was just like, wait a minute, what? So brutal over the years.

Barry (17:14)

Yeah, yeah, yeah. ⁓ the crashes would be so bad. And like, it's

like, and we're still using I mean, it's changed to animate. But like, we've we've tipmouse is still using it. We still use like, you know, it's funny that they never used to like, I feel like animators were like the bastard children to the Adobe or to the Macromedia Flash suite, essentially. Yeah, right. And now it's like supposed to be made for us. But I feel like the animate yet now they're like, they have they have no

Mack Garrison (17:22)

Sure, right.

I think we still might be, honestly.

Barry (17:42)

There's nobody else using it except for the animators. now like, like they have to. Yeah. Yeah. But, ⁓ you know, whatever code they used, like after effects flash and all that stuff, like whatever code is still in there is still super flexible and still, you can still do like a lot of amazing things with it. So it's, it's, it's, it's no wonder like we're still using it.

Mack Garrison (17:43)

Right. They're like, all right, I guess we'll add some features you guys want to hear. Whatever.

You know,

a random sidebar question because we kind of experimented this a little bit. You know, what we do a lot at the studio is a little bit more on the corporate side, but every now and then we get to do some sell work. And for a while we experimented with animate, we did harmony, we did TV paint. Do you feel like from Titmouse's perspective, like have y'all leaned in is is animate where y'all want to be? Do think that's like the best industry standard or do you feel like flexible that all three of those kind of have their time of day in certain instances?

Barry (18:16)

Mm-hmm.

I think it's a B, it's exactly what you said. I think maybe at some point, animate was gonna be like the all in thing. I think with, we do animation in house, we do animation overseas, there's no like one way we do it. And I think that's kind of the, maybe that's the special sauce, is like learning to be flexible. Cause I've had projects where I've got an animator animating in Clip Studio, I've got an animator animating in...

Mack Garrison (18:49)

Yeah, true.

Barry (18:59)

I've got one animating in Flash. the kind of, I mean, what I learned from that is like, oh, anybody can animate in everything they want as long as we can bring it together and kind of clean it up in color in the same way. Like once we do that, like we can get it into, you know, After Effects or whatever final suite you need. like, yeah, generally like if you need that talent, like the talented animators, you might need them to work in whatever they need to work in so that they can work as fast as possible. Yeah. Yeah, yeah.

Mack Garrison (19:07)

Yeah.

Right, because you just need them to move quickly and whatever they feel comfortable in. Because oftentimes,

like I guess with deadlines, it's like, yeah, we can't mess around with trying to learn new things or get people on the same platform. It's like, let's just move and go, right?

Barry (19:28)

Exactly.

Yeah.

And I think, I know that Blender's like has, has burned a lot of excitement being free and grease pencil and stuff, but I still haven't, I know, know some movies and features have been made successfully a hundred percent in Blender, but I know being a big, you know, Tim House is pretty big and it's like, like, I mean, employee wise, like it's big. So it's like, it's hard to move that like boat into something. So we're always trying to find like some small project that we could kind of do a little bit more experimentation on, but.

Mack Garrison (19:36)

Yeah.

Sure. Right. Yeah.

It's interesting,

mean, like even Blender from like a 3D standpoint, know, we were always kind of Cinema 4D that was kind of go to for the more motion graphic work. know, Maya's always been there for like character work, things like that. But it is interesting seeing just like what this newer generation is coming out of school. Like, look, I don't have any money. So I downloaded Blender and this is what I'm making. You're like, wow, that's actually like not too bad. know, Fidelity, this is pretty good, you know.

Barry (20:04)

Yeah.

Yeah.

Yeah.

Yeah, yeah. It's like, it's as long as you can figure out how to like connect to the other programs that you may need. I think, I think, I think you're in a good, you can, can learn how to use it and make it flexible. That's okay. That's all technical stuff. I get it. I love it.

Mack Garrison (20:23)

Exactly.

Well, I definitely took us down this like 80 D rabbit hole on like on technical stuff. was there. I was interested

in doing so let's go back. All right. So you're, you're out in LA. You're kind of getting this generalist knowledge. Let's fast forward a little bit. Cause I don't want to spoil too much that you might talk about at the bash. ⁓ you get over to tit mouse. ⁓ when did you first arrive at, at tit mouse?

Barry (20:47)

There was a cartoon that they were making called Motor City, which was one created by Chris Panoski, the owner of the studio. It's like a show he's been working on since the late 90s. tried, he used to work at Liquid Television back in the day and he made a show called Downtown. And, you he worked on like Beef and Butt Head and Dari and all that stuff back in the day. But he was, he's been making the show for a while or at least trying to pitch it.

Mack Garrison (20:51)

Mm.

wow.

Yeah.

Barry (21:14)

develop it and some of his creative execs from MTV Liquid Television work at Disney now. And they were like, hey, you still got that Motor City thing kicking around? And instead of like, they used to have cigarettes and tattoos and shit, but now it's like they made it a little bit more kid friendly, but it was like a cool show. It looked amazing. It looked like...

Mack Garrison (21:35)

Sure.

Barry (21:38)

It looked like Robert Valley designs and crazy extreme cars and stuff like super fun, like stuff made for toys, you know? But like all things, I've learned most in this industry is like, it's really hard to get past one season, like first season. So like it only lasted one season. It came out when like the Tron cartoon came out. So it's like another kind of Robert Valley, like two Robert Valley style shows that were coming out.

Mack Garrison (21:42)

awesome.

Yeah.

yeah, that's right.

Barry (22:05)

It was a mix of 3D, 2D, and that was like the, when I started working there and working on that show was kind of when I opened my eyes, like, you can do cool, dramatic stuff in animation. Like I always thought it was like, that's only in anime, which is, not in the US, but that like Motor City was an eye opener just to see like how you could push, you know, storytelling and animation in digital space and flash and all that.

Mack Garrison (22:18)

Right.

You know, it's interesting, like, you know, you're talking about just like how you can be dramatic in animation. Do you feel like the U.S. has kind of lagged behind in that? Like I remember watching like Akira for the first time, you know, and like just being like, holy cow, this is insane, right? It's just not even having an idea that that even like existed. Do you feel like we've been playing catch up into that a little bit compared to internationals? Or do you feel like we've kind of got, you know, caught up now at this point and kind of what we're doing?

Barry (22:42)

yeah.

I mean, I feel like it's just, more of the minority than it is the majority here. Cause it's, it's, it's hard to say we've been playing catch up in that. I just feel like even with lower decks, Star Trek, lower decks, like it's an adult cartoon. It's adult comedy, but like, I feel like, I don't know if it's a cultural thing or what, but there is like the moment someone hears it's a cartoon. It's kind like the checkout. Like it's like, it's, either a kid's thing or it's one those stupid Simpson shows or something like that. like.

Mack Garrison (23:08)

Right.

Mmm. Yeah.

Mm-hmm.

Barry (23:26)

There is like a definite, like a more like an envious, like, spectrum of anime and manga that they make over there, like for all, like for kids and for, you know, they can teach you how to cook, you know, like there's anime that'll teach you, you know, how to play tennis, you know? Like there's, there's, there's things that are, there's a, there's a bigger spectrum over there of what's considered, you know, quality animation material or manga material. And I don't know if like,

Mack Garrison (23:38)

Yeah. Right.

Barry (23:56)

I don't know if it's our cultural interests or where we've just trained everyone to say like cartoons or Disney and that's it. I feel like it's a little bit of that because we still have dramatic mature comics. It just feels more like a niche audience thing. I feel like, mean, the more that kids are into...

Mack Garrison (24:02)

Right. Cartoons are for kids or whatever. Exactly.

Barry (24:19)

Like they have more access to anime and manga than we ever have. like it's, it's, it's, there's proof in the pudding that maybe it's just maybe a boomer generational thing or something that like the kids will, who are into all that stuff now will still be into it later. Cause adult swim shows all that stuff. it, still just, it's just a minority. feel like getting mature series off the ground is, is definitely more difficult, but we've done it with, you know, Joe Bennett and scavengers rain and the new casual common side effects is awesome. Like that's kind of, to me, it's all that's.

Mack Garrison (24:33)

yeah.

Mm-hmm. Yeah.

Yes, badass.

Barry (24:48)

That's definitely in the right adult drama. There's drama, it's a comedy too. There's some lights that are shining, some bright lights that shining that are more for that mature animation side.

Mack Garrison (24:59)

Yeah, 100%.

Well, like you alluded to, know, Star Trek lower decks, you know, and like people, it's coming a bit more mainstream in some of those ways as well too, that are bringing more people in. You know, you've worked on, you know, I'm looking at all the different projects that you've touched. I mean, you've done so many cool things. This is kind of a big loaded question because it's hard to pick favorites or anything like that. But I'm just curious, you know, thus far in your, you know, the 18 years or so you've been animating, do you have any like favorite moments or favorite projects you've been able to work on that you're just like, yeah, all this stuff is cool. I'm so proud of everything I've done, but just really especially

like being able to work on this or what I did with this project.

Barry (25:35)

Star Wars was a biggie. It's funny, like Star, Star Trek, Star Wars, like I kind of get into this, there's things that start with Star. But Star Wars and Star Trek were pretty special because like, I feel like you can't be like, you know, there's always the stigma of like, can't be a fan of both or everybody, but am a fan of both. Most people are. And getting to play in the sandbox of both those worlds was pretty incredible. And it's not something I ever thought.

Mack Garrison (25:39)

Mm-hmm.

haha

Sure, right.

Barry (26:03)

would happen, you know, like that's there's still like a bit of that nostalgia member berry stuff happening when I'm when I'm doing that and like just trying to like make like the version that you wanted that you you know, I imagine there's other kids or whatever like that are there. Me now, you know, watching whatever they're consuming now and just like hoping that you're kind of like, you know, trying to set them up or make like those member berries now like for the for what you want them to watch when they're older, maybe inspire them to make stuff that like

Mack Garrison (26:07)

Yeah.

Barry (26:33)

similar, like it's part of them to make it feel, make those properties feel as like magical as they felt to you when you were smaller.

Mack Garrison (26:41)

Yeah, 100 % because I think it's still easy. Even though we're all kids inside and we're operating this play box of animation, which is super fun, there's still the politics of the stuff that we deal with and stakeholders and all sorts of stuff. And so it's easy to feel jaded and being like, fine, whatever, we'll just do X, Y, Z, right? If it just appeases everyone. But you know the 10 year old is like, no, you gotta do this. The guts have to come out of the hand or whatever. Which I do look, yeah, sick, nice, nice, yeah.

Barry (26:53)

Yeah.

Mm-hmm.

Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah,

Mack Garrison (27:10)

Someone told me one time, know, the best place to be in life. This was actually a quote from my executive producer. So Marin, if you're listening to this, thank you for this. She said the only two people that you need to make happy in your life are, think it's like your eight-year-old self and your 80-year-old self. And I really love that because it's like, you know, the 80-year-old self is probably saying like, look, don't work too hard, relax a little bit. And the eight-year-old self is just like make cool stuff, right? And I feel like with what you're doing, you would echo that sentiment, but I don't know, I'm gonna put you on the spot. Do you think you're impressing your 80-year-old self and your eight-year-old self?

Barry (27:22)

That's good.

I think there's some moments I've done, I'm pretty, I if you're like, if a lot of us are similar, I know that we all have like a lot of anxiety and self-confidence issues and I'm like overthinking every frame of what we're making and overthink, but I think there are some moments where I'm like, I think I did pretty good on that. Yeah, I think so. I mean, there's also like a big asterisk on all of this that's like, our egos are still pushing us to like do this stuff. Like we think we can do this stuff. Like we think we, like I think I can do this. Yeah, I'm the one who can.

Mack Garrison (27:49)

Right.

Yeah.

Yeah.

Barry (28:09)

do this and nobody else would be better at it than me. yeah, they're still like, like, even though they're like all these like manic issues in your brain, they're still a big asterisk that's like, no, I can do this. Yeah, yeah, yeah. No, you could do this. Yeah, yeah. I'm the one who's right. You know,

Mack Garrison (28:19)

Yeah, 100%. Well, we

get so caught up in looking ahead on what we wanna do, or when we do look back, it's what we wish we would have done. I think that's a big thing. It's like, I wish I could have done this, but so rarely do we ever be like, yeah, I crushed that. Look how great this is. I'm proud of what I made here and this time and energy I put into it.

Barry (28:27)

Yeah. Yeah.

Yeah, yeah.

Like, I don't know if you have to like end up rewatching anything you've done in the past and just like, I didn't fix this. I can fix that. my gosh, look at that line thickness. That's way off. Yeah.

Mack Garrison (28:41)

God, yeah.

Oh, 100%.

You you catch like the little error and you're like, did anyone else see that? And you're like, I'm just going to pretend I didn't see that or whatever.

Barry (28:50)

Yeah. Yeah. Or

like, a fan or like an audience member catches something you didn't and it's like, know how many, you know how many we fixed like 180, you know how many, like one, how much stuff we fixed just to mess up that one time, you know?

Mack Garrison (29:03)

I know. ⁓ I know. It happens.

You know, none of us are perfect. You know, and you look at something a million times and you kind of become blind a little bit to it, right? You know, this is a random question for you all. How do you all do like a QA process when you're like shipping stuff? I mean, is it basically like everyone looking through it and like going, are y'all going like frame by frame on stuff to analyze it?

Barry (29:23)

You mean when you say shipping, you mean like shipping stuff to an overseas animation studio to do? Or you mean like, like, or delivering it to like for TV broadcast?

Mack Garrison (29:30)

Yeah,

yeah, let's say delivering for TV broadcasts. Like, so this is like final step before this sucker is like playing to go live. Like, what does that process kind of look like? I'm just so curious.

Barry (29:32)

Yeah.

Yeah, so we call them take ones or take twos, like every time it's just like me, my art director, editor, producer, animation supervisor, where once we kind of get like a full cut of the show, they call it a take one, like when it's a first pass, where it's like every single shot is animated, you know, it's not 100 % there, but it's kind of the first time we're looking at it as a whole piece. We're literally just going shot by shot. Anything anybody sees, like you call it out, like just, we don't want to miss anything.

Mack Garrison (29:50)

Mm-hmm.

Barry (30:05)

I'm calling out probably the most, just being annoying. Lately we've been using Sync Sketch. I don't know if you use that. Yeah, yes. Just going frame by frame and just drawing notes, notes, notes, notes. Got to do this. This is for animation to fix. This is for background to fix. And then the editor on top of that is putting all this stuff together. But we also have a QC department. CBS has a QC department where they're calling us out on like...

Mack Garrison (30:28)

Sure.

Barry (30:31)

more technical errors, they're catching smaller things that we're missing, text errors, things like that. And it's kind of like we do a take one, take two, take three, you know, while we're locking, like where we're all just watching everything over and over again, excuse me, by the time it's come out, we've watched, I don't know, I feel like I've watched those shots all like a thousand times over, you know, like, yeah.

Mack Garrison (30:32)

Hmm.

believe it, because it's hard. Like you watch it for

the 10th, 11th time and you're still trying to like see if you catch anything, right?

Barry (30:56)

Yeah,

and it's like there's three to four hundred shots a show times ten, four thousand, five thousand shots sometimes. We're going through a season. It's like it's hard. there is just like a QC process. Like we also had to do one that was for I don't know if you've had an encounter before. It's called the Harding Test. It's like seizure, like checking to make sure no flashing frames and.

Mack Garrison (31:16)

Yeah, we've done

some stuff through some like ADA compliance with a lot of like websites and things. There's some various pieces that we look into, but that's interesting. So what's the process of that like?

Barry (31:25)

It's, I mean, it's also, I've been working with, worked with it since Disney. think, I forget if it was cause of Pokemon or some project, but it's software. It's essentially like Disney has licensed it or so, or so and so has licensed it. And when we submit it for the final piece, like they submit the whole episode and they kind of just run the whole episode through the software. And it kind of gives you a readout of like, this is red flashing frames. This is like white flashing frames and tents.

Mack Garrison (31:30)

Mm-hmm.

Barry (31:54)

We kind of have to go into After Effects and fix it. We're lucky that we can change it in shots, but there are times where they call it a... Sometimes it's like a post house that just does a blanket fix over everything. like, I don't know, if you ever notice... Yeah, if you never notice on like... You'll see it on like some Netflix shows or maybe a Prime or whatever, you you're streaming where all of a sudden like maybe something goes by fast and it gets weirdly gray. If you ever notice that, you'll be like, oh, that was like a post house. That was a post house seizure fix where they just...

Mack Garrison (31:59)

Yeah, right.

⁓ like a film over something basically.

yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah.

Barry (32:22)

kill the contrast until like it passes the test and then it goes back up again.

Mack Garrison (32:26)

Because

they're basically like, yeah, we can send it back to them or we just put this fix on just keep it moving forward and they do that.

Barry (32:31)

Yeah, because sometimes

they might be getting these licensed shows or whatever, like they might have been done a year from now. It could be something from 10 years ago that they're having to do that too. Yeah, yeah. But they could do it better.

Mack Garrison (32:39)

Right?

Right, crazy. ⁓ that's so interesting.

yeah, of course, of course it can, but yeah, that was really interesting. mean, like even on like a smaller level with what we do, I mean, there's similarities, but yeah, I mean, I imagine for broadcasts, especially big broadcast stuff, it's like you've got the whole, the whole like CBS team looking at stuff. You got y'all looking at it. It's just a million different eyes, which is really interesting. Well, we're coming up on time here. I got one more question for you. I'm always so intrigued on.

Barry (33:05)

Yeah. Yeah, yeah, yeah.

Mack Garrison (33:13)

who some of the people that I'm inspired by, who are they inspired by, right? I mean, there's so many folks coming to the Dash Bash who are gonna be pumped to hear from you what Titmouse has done, what you've been able to do. I'm really curious from your perspective, you know, who are some of the folks either today or even growing up that really inspired you and your work?

Barry (33:30)

The owner of the studio, Chris Pernaski, is a pretty big deal. His attitude, his overall vibe is really good, just as a person, just to try to learn how to be comfortable with people and make them feel comfortable. That's always hard. Like I said, we're all manic artists stuck in their caves and stuff, so it's like, how do I be a person again? So people who are good, you're pretty good at that, just making people feel comfortable. People like that are really inspiring to me.

Artist wise, the comic book greats, dude, it's like, I don't like, I say comic book names, I'm like, I don't know, do people know these people anymore? Arthur Adams, like, was a huge inspiration to me. He's a comic book artist from like, he's still around, he's amazing, but like the heyday was the 80s, 90s. Yeah, yeah, he pretty much like, there's like an X-Men image that's like, it's probably the most repeated.

Mack Garrison (34:13)

Arthur Adams, he was big on X-Men, right? Yeah.

Barry (34:21)

you know, put on t-shirts, put on lunchboxes, put whatever, it's his X-Men, like it's his, it's his X-Men, he's the best. I'm trying to think, I mean, there's the big guys like Jim Lee, all those 90s artists were super important to me. Joe Madiera was like a big X-Men artist for some reason, we're always the... Yeah, yeah, yeah. Try to think of, man, there's so many.

Mack Garrison (34:23)

Sure. Okay, nice.

Mm.

Well, X-Men was badass, dude. 100%. Like, that's why for sure.

Barry (34:51)

I mean, there's movies that like completely kind of rock my world and maybe like Paul Verhoeven is one of them, like RoboCop, Alien, Aliens. Like, yeah, like, so like, it's like, and those, yeah.

Mack Garrison (34:56)

Yeah. dude. All the aliens 100 % alien and aliens, dude. That was like I

was obsessed with that and like Predator as a kid like those two I was like sick.

Barry (35:07)

Yeah, Predator, yes.

Arnold Schwarzenegger is super inspiring to me, dude. He's the American dream because he's a guy who came from another country and became a freaking governor and is a movie star. Arnold Schwarzenegger is huge inspiration. But no, those movies like Paul Verhoeven, Ridley Scott, James Cameron, they're all like, I always look at them as directors that like, oh, they show me what I want to see on screen before I know it. Before I know that's what I want to see, there's like...

Mack Garrison (35:31)

Mm, yeah.

Barry (35:34)

There's something satisfying. There's always a lot of payoff in their movies that pays off really well. I think I'm always hoping at the moment to be able to make something as great as them.

Mack Garrison (35:36)

Yeah.

Dude, 100

% in their attention to detail in these pieces and you can tell it's their vision on what they want it to be, which is really good. I'm always so empowered by folks who have such clarity on what they want to make, because it's a really hard thing to do. Like, what is the right decision? What do want to do? Those directors can get in and like, no, it's this, this is the world, this is what's happening. I mean, that's really incredible.

Barry (35:46)

Yeah.

Yeah.

Yeah, you're just hoping for the chance to do that yourself, just to make that clear vision, like you're saying.

Mack Garrison (36:11)

Oh man, well I love it. Well everyone, we've been talking today with Barry Kelly. He's a nerd from Nebraska who also happens to be an Emmy award-winning artist working in animation for the past 18 years. Director at Titmouse makes phenomenal work. Barry, I enjoyed chatting with you so much today. If you want to come see Barry, you still have an opportunity. You can get your Dash Bash tickets June 11th through 13th, 2025. That's this year, believe it or not, it is 2025 in Raleigh, North Carolina. And if you've never been to Raleigh, let me tell you, it is great.

Barry (36:24)

Thanks, man.

you

Mack Garrison (36:36)

It's East Coast. We've got a little edge to ourselves, but we're still tucked in the South. So if you're from the West Coast, you know, we're friendly. It's easy. You've got great food. You'll have a blast. Barry cannot wait to hang with you later on this summer.

Barry (36:47)

Hey, thanks. Can't wait to see y'all. I'm excited. Let's do it.

Mack Garrison (36:49)

Thanks everyone.

Take care.

Meet the speakers: John Roesch

An interview with John Roesch: Lead Foley Artist at Skywalker Ranch and co-founder of Audible Bandwidth Productions.

Q&A hosted by Meryn Hayes & Cory Livengood.

Read time: 15min

Meryn:

Meryn Hayes: For those who don't know you, could introduce yourself.

John:

Sure. My name is John Roesch and I'm a professional Foley artist that has been working in the film business for almost 44 years now. Playing in a big sandbox, making sounds that if I do my job right, you don't know I've done.

Meryn:

Foley is one of those jobs that people don't tend to appreciate until they hear a movie without it. We're really glad that you're joining us to talk about such an important part of the entertainment industry not many people know about.

John:

Well, I'm glad I am too because like you say, Thor is running towards saving the day, so to speak, and we're close up on his feet and he's running really fast. And wait a minute, if there's no sound there, I'd be like, "Is this guy really a hero?" Or same thing for a gal. So our contribution, and of course we're a small spoke on a big wheel, can lend credence to giving a sense of reality because of course, as we know, all filmmaking is just that, it's smoke and mirrors. But we want to make sure that you, the audience, feel that you're completely immersed in it and it's "real" to you.

Cory:

I'm curious about how you found yourself in this part of the filmmaking process. I know you dabbled in acting and directing at a younger age, how did those skills translate to Foley if they do at all? And how did you end up in your big sandbox, as you say.

John:

I was an actor in high school and I went to NYU film school and then I went to the American Film Institute thinking I'll be a director. And just so happened that a gal that did my script supervision for the one AFI film I did, she said, "Hey John, I need help doing sound."

And next thing I know they look around and say, "Well, this guy's got sneakers. Are you a runner?" I said, "Yeah." A guy goes, "Well, this film has running in it. Come to the Foley stage." What is that? The Foley stage? "Come to the Foley stage." Okay. So I show up and they say, "See that guy on the screen there?" Yeah. "Okay, run for him." All right, so I ran across the room. They said, "No, no, no, you have to run in front of the microphone. Like, "Oh, I see." They're going to record the sound. I went home that night and I thought, "That is the stupidest job ever."

And next thing I know, I get a call from her husband, Emile and he said, "Hey, I really like what you did. Can you come in tomorrow to this other stage, do Foley?" I thought, "Okay, I guess." So I'm leaving my place in Venice, California and I had a convertible, I was backing up and, oh, there's the landlady. "Hey Joaney, how you doing?" She says, "Hey Johnny, where are you going?" I said, "I'm going to the Foley stage." She's not going to know what that is.

Cory:

Yeah, of course!

John:

She says, "Hey, that's what I do. They just fired somebody there. Maybe they'll hire you."

Cory:

Your landlady?

John:

I thought, "Man, has this got kooky or what?" I'm not so sure. So I said, "Yeah, okay, sure. Thanks, Joan." So I drive off and do that. I get home and on my answering machine, the low budget film I was going to AD got pushed back out to three months and rent was going to be coming due. I thought, "Well, maybe I'll just call Joan and just see what happens." And that was 44 years ago.

Cory:

That's incredible.

John:

To answer the second part of your question, it indeed is important to have a bit of the thespian in you because the hardest thing to do are actually footsteps, to give them life. And to do that, you have to kind of act, if you will, that part of whoever's on camera. Are they a little drunk? Are they the hero or heroine or are they the bad guy or the villain? You're trying to embody something that's not there. You're trying to give soul to something that's not there. And that really comes from acting. So yeah, there you go.

Cory:

Yeah, that's interesting. Anytime I've seen video, probably of you before we met, of course, on television of Foley being created, it always felt very performative to me, like an actor in a way. And almost no matter what sound is being created, it's always very interesting.

John:

Yeah, it is by definition. In fact, it's called Foley named after Jack Foley, that is, in deference to him. But it was not called that. It was called the sync effects or the sync sound effects or the sync stage, or actually the A stage was a stage where they did a lot of what we now call Foley. But the true definition of Foley is custom sound effects. That's a differential between a jet plane's engines going by and then somebody grabbing the throttles with their hands and pushing them forward to make sure they clear the obstacle in the distance. Grabbing the throttles is unique to that moment in that film on a per-film basis, whereas the engine spool up, that might come from a library, it could be used in many films. But Foley has uniqueness all unto itself, hence the, as you just said, the performance aspect to it.

Cory:

Do you recall seeing or hearing a film that really inspired you from an auditory perspective when you were sort of starting your career?

John:

Oh, I say 2001 would have to be one of those. Just the way it's portrayed. Space and all that sound kind of in the background and then bursting into the back into the craft. And there's no sound there. I mean, it really kind of leapt forward for me, and I'll tell you all this now, I didn't really pay that much attention to sound until I got into Foley. I was more interested in like, "Okay, how do you block this scene?"

But of course, as time goes along, in fact the measure for me, if I'm watching a film and I start picking apart the Foley, that means I don't like the film.

Meryn:

Is there a particular project looking at the portfolio of work that you've done in your 45 years that you hold as one of your favorite projects or a few different favorite projects, and what would be on that list?

John:

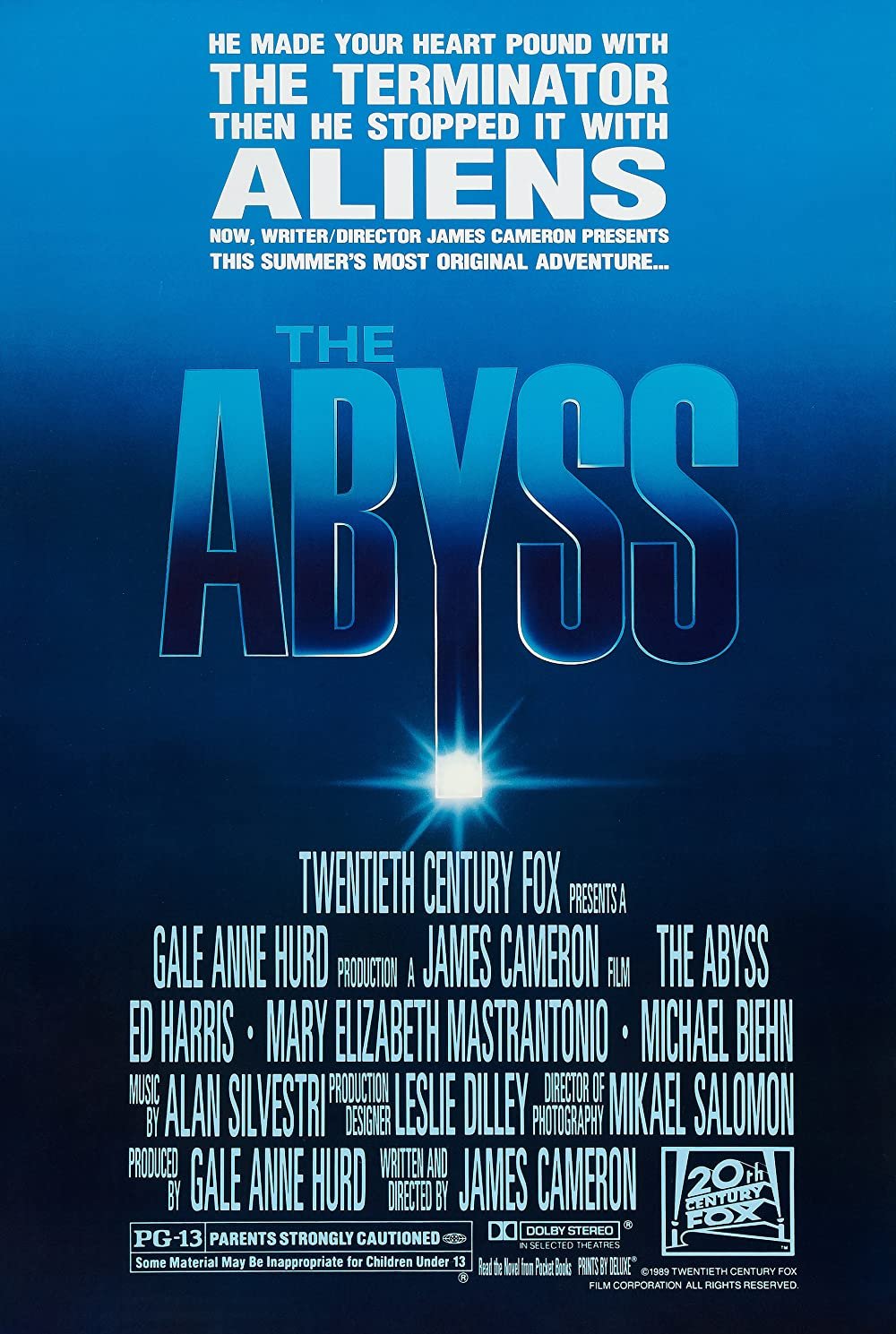

I'd say there are three or four if I could go into that many. One of the hardest ones was a picture called The Abyss and that dealt with a lot of underwater water. And that's extremely difficult because that's an all-encompassing sucking of the frequencies, if you will. So we had to really experiment with that to come up with what's going to work. And of course, James Cameron, you do not want to disappoint him. And I've got a story which I'll probably hold back, maybe I'll share it during the meet and greet. We'll see.

Cory:

Now I'm curious.

John:

Good. I’ll whet your appetite. Another one, and I'll kind of put those two together would be Back to the Future, and Who Framed Roger Rabbit,. We’d been in a bit of an arc where Foley was really not used that much. And during those years, I call them the Camelot years of Foley, we were given license to do everything.

So when the plutonium is being sucked into the plutonium motor, if you will, on the back of the DeLorean, that was us using glass and certain effects in even a blooping sound. If you take a cardboard tube and you kind of hit it on one end, it can make a [bloop sound]. Things like that, which typically you wouldn't do in a film.

And Who Framed Roger Rabbit, there again too. You had not only humans walking, but you had toons. So we had to do a whole section from them, not only their footsteps, but their props. And that was really just a whole heck of a lot of fun.

One that I think is very important, would be Schindler's List because that's a period of history which we should never forget, I think.

And of course these days talking about animation, Soul is a particular project which I'm absolutely thrilled with. It really embodied a lot of things that are difficult to do for animation, and they were just so beautifully done. And I'm not talking about our aspect per se, although we had a chance, again, we had the time to do it.

And of course, you could take a Marvel film, something big, over the top. Think Guardians of the Galaxy type thing. So those are fun.

And last but not least, there would be what I'll call the student film. And I did a film many years ago called In The Bedroom and Todd Field was the director. And that was something we really did kind of bootstrap that not having much money, if any. And we did that kind of in the off hours because I believe that I... I saw it and I knew this is an incredibly good piece. By the way, if you haven't seen it, I would recommend it. This guy's going on to direct Tár and he's up for six Academy Awards.

Cory:

When you first get a project, walk us through what that process is from the very beginning when you're just starting up until you get to “we're in the studio now, we're making the sounds”.

John:

Okay. Well, we like to beforehand get a look at the film if possible. If we can't look at the film, we would at least like to get notes from the director. And there's something called a supervising Foley editor, he, she, or they, that are given guidance by the supervising sound editor, sound designer. Like, "Okay, in reel one, we want to cover these feet. We want to have you do the pickup of the special sword, yada, yada, yada."

So they will impart that information to us and also talk about the design of it, so to speak. Let's say in animation, if it's a cat running around, if it's a main character, even if there's not a little license or bell or something on it, we might try to cheat something there to give it life. But is that contrary to what the director wants? And then when the day comes we start, we'll look at the reel again and we'll have what are called queue sheets. Which will detail out Heidi on channel one, Dave on channel two, Christo the Cat on three. It'll detail out what we need to do. Footsteps first, then prompts, and then movement, if any.

When I say movement, it could be a leather jacket, which is... Let's see, a Guardian's [of the Galaxy], they wear those type of things, so that would be a separate prop. Whereas if we're just covering general movement, let's say for an animated feature, we might just do a one pass cover.. And that's how we proceed during the day.

And it could be that the director said, "I'm not really sure how I want Sally's footsteps to sound there and overall the feeling of her character." So we might try variations, we might try tests. So we'll do test A, B, C, D and just send them off. We won't say what we used. Test A's a tennis shoe, test B is gloves. We'll just send them off and then the director or whoever will get back to us and give us their feedback and we'll go from there. And that'll be established throughout the film.

Cory:

And how closely are you working with the director? Or is there any case where you're working with the music composer or is that a pretty separate situation?

John:

Typically, music and Foley, the twain don't meet. The only time they do in a sense would be, let's say with David Fincher, because he's very involved in all aspects. So he'll make sure that Trent Reznor or whoever is doing the sound is involved with Ren Klyce, who's typically who he uses. And then they will filter down to us what they need.

So typically we'll start a film, let's say... I don't know any of the recent films. Strange World. And maybe a week into it, they'll fly up to Skywalker [Sound] and sit down with us and play some stuff back. They'll play back some of the Foley and review it and if there's any changes, let us know. Now, mind you, again, if there's something we think we're really not sure about, we'll send a test down first to make sure we're on the right track, because time is of the essence.

Meryn:

And what about in terms of how long a project might take? I mean, I know it's a process, but say for Strange World, for example, I mean are we talking weeks or is it a one week and you're done or is it months?

John:

No, it's typically two days, maybe three days a reel. Now, Strange World, if I recall correctly, I think that was 18 days, all told. Whereas the last picture we just did, unfortunately, I can't name it. It's volume three, I can say that. I think that was 20 days altogether. And Pixar films tend to be even longer, like 25 days, which is really necessary because again, in animation you can get away with things that you really can't do in live action to some degree, which is wonderful.

Meryn:

I love that you said 18 days was long because in my head I was like, "That feels very short." So I think that's just a good reference point.

John:

Well, I don't know that I'd say it's long, but I'd say that probably is enough. I mean, given our druthers for animation, any project that comes in, we'd like 25 days because then we know it's going to get covered. And we also work of course on commercials, on video games, and a little bit of television that is streaming. Worked on Andor. That was three or four days per episode, if I recall correctly, which was necessary. Again, because I have a lot going on there. But if you're a Star Wars fan, I highly recommend that.

Meryn:

Yes, we are big fans.

Cory:

Maybe one of the best Star Wars shows that's been put out there yet. In my opinion, anyway.

John:

I would agree and I think season two's going to be even better.

Cory:

That's great. Looking forward to it. I'm sure you won't give us any spoilers, but...

John:

My lips are sealed.

Cory:

Well, speaking of Star Wars, I mean, I'm definitely curious about your process when you're coming up with the sound for something that's totally fictional. A laser gun or a spaceship or something that doesn't exist.

John:

When I see something on the screen, I hear its sound, so then I try to translate in my mind, well how do I create that sound? So like you say, if I'm picking up a weapon that's specialized or loading it, what would that sound like? And is it a used world like Star Wars or is it a clean world like Star Trek?

I'm going to want to embody the world itself and stay within those contexts, within those confines, I should say. And of course, the great thing with Foley, there's no rules. The only rule is there are no rules. So you can try something. If it doesn't work, do something else. That's the beauty of it. And so that would be in essence the process.

Meryn:

Is this a professional hazard where you're just going about your day, you're in your kitchen and you put a cup down and then you hear something and you're just like, "Yeah, I need to write that down 'cause that sounds like..." Your friends and family just like, "Oh, John's always stopping what he's doing and he's writing down that piece of paper that fell, sounds like a bird's wings or..."

John:

Every once in a while, something will happen where something will be delivered or who knows what, and it gets pushed a certain way and moved a certain way and I go, "Wow, I'm going to have to remember that and take it into the stage." And conversely, when we're working on a film, if we establish an unusual prop, I'll take either a text note or a picture of it or even do a video. In fact, Shelley might stand over me and I'll explain what I'm doing, how I'm doing it so I can recreate it throughout the picture and vice versa for her.

Meryn:

Yeah. That's amazing. Is there something that's a really strange sound that you can recall...

John:

Well, I'll tell you the Abyss story then 'cause I think it was probably the most difficult sound, one of the most difficult sounds I've ever done. In the picture, Ed Harris is sitting down in a suit that's now going to have a helmet latched on, and it will fill up with liquid, literally starting at his chin, up over his face, over his head. And he'll then breathe that in.

And the reason for that is that it's going to allow him to go to deeper depths than one could without being crushed. Anyway, that's the theory behind it. So there I am, looking at this going, "Okay, now if I hold a helmet upside down and I take water and pour it in the top, it's not going to sound right. It's not going to sound like a muffled helmet, it's going to sound like [clear]. So how do I do that?

I thought and thought and thought. The night before our last day of Foley, I had a dream. And I dreamed how to do it.

And the way to do it was micing in a certain way, where I was stealing the ambience of a helmet and yet having a way to pour into something also that would approximate a helmet so I could literally get the proper going from low to high up over his head. And then on a separate channel, I took a straw and did a couple bubbles to come out of his nose. Strange job, I know.

Cory:

Are there any big differences in your mind when you're working on a film versus television versus a video game?

John:

Well, yes, certainly a video game has a routine all of its own. And that could be, are we doing the cinematics or are we doing the in-game assets? So if it's the cinematics, we approach it just like a feature film. If it's in-game assets, we might do Batman's cape or 2 or 300 variations of it, one after another. Or footsteps just landing on a surface, on metal. We might do 50 or 100 of those because again, during game play, randomly it'll be pulled from the bucket as to what particular sound that one step is.

So that's very intensive for a Foley artist team to do. Versus if you work on a feature, it's kind of tag team, if you will. And now mind you, television is a bit of a different beast, because not so much when I mentioned about streaming, at least at Skywalker, but television itself doesn't typically have a budget that's as friendly as one would hope.

Meryn:

You started talking about the team just there. I mean, on average, how many people are kind of working together on this? Because it sounds like... I mean, you mentioned earlier it's a team effort.

John:

Totally. The day starts as a team and it ends as a team because even if I'm doing footsteps, Shelley is either helping run the sheets with Scott or Scott's what we call driving. He's telling me where we're going to go,. But she might be making notes for shoes for herself or certainly for doing props. While she's out doing props, I'm in another area looking at a monitor, looking at the actual reel, making notes for myself going, "Okay, so this cut... Actually we're cheating the hand grab of Thor on Loki." we’ll not actually see it, it's just literally on the cut. So I'm going to approach it a little differently than I would if I see it. Or the communicator that's being picked up and is being flipped out that has to have a certain sound to it because I'm seeing some detail here.

Mind you, while she's out there working, then we switch. So she'll do the same thing. She'll be in the monitor checking her notes while I'm actually performing. So that's exactly what happens. Does that happen at all for all of Foleydom? It's hard to say. You have a younger generation that I don't know that knows the joys of having a team.

So point being, I think it's a lot harder in a sense for younger Foley people, especially if they're just working by themselves.

Meryn:

That leads very nicely into the next question that was going to be about advice for younger Foley artists. And maybe the advice is to find people, find your team. Is there any other advice or things you can think about for people who might be early on in their career or wanting to get into this field and they don't know how?

John:

Certainly if one wants to be a Foley artist, I think number one, they need a good background in acting. Take some acting classes. If you can, direct some one-act plays and read a lot. Read Shakespeare, read just a lot of good books and watch films. AFI top 100. Pick them apart. Why do you like this? Why do you not like this? Take a television show, like Friends, and then just put down something to walk on. Because typically Friends is people walking in from off stage and stopping or leaving or maybe walking upstairs, so you can practice getting sync, not worried about the sound that has to really come on a Foley stage.

And of course Mom and Dad out there won't necessarily like this as much. A half hour a day of a first-person shooter video game is okay because you're literally training your eyes not having to look down at your hands, which is extremely important for doing Foley, performing. And, you'd want to have aerobics in your life along with stretching. Aerobics-wise... Swimming, you can't beat that. All those things are really mission critical to be an excellent Foley artist.

Hopefully then you can get on with someone who can mentor you and learn from them. And then also try out your own thing because nobody has the actual answer. It's in a sense experimentation and you'll find your path that way and having a belief in yourself and also being open.

I didn't go out and start out to be a Foley artist, but look where I am. And I don't say this to dissuade anybody from being a Foley artist, I'm just saying just be open. Hopefully you'll have a love of it because I think it's no longer a job, it's a career. And then surround yourself with people that'll hold you up. Because you don't want to be with people that are jealous, either overtly or covertly. That'll do you no good.

And those are people you really don't need in your life because there are people that are going to want the best for you because they realize, "Hey, if we work together and you're doing great, I am too." And why not? Especially these days in this world. Good grief. Hey, I'm going to be 69 by the time I see you all. I've learned the four words, "Be happy, love fiercely." That's it.

Cory:

That's great advice. it's just really interesting and something I hadn't thought of until we met and started talking about this stuff, how the hand-eye coordination, the aerobics, the performance of it and all of that is just a very different viewpoint when it comes to post-production and even audio, to a degree, which is really, really fascinating. It's just so much exercise, which is great.

John:

It's helped a lot, I'll tell you.

Meryn:

I have a burning question from my five-year-old who we watched Strange World for the fifth time last night. What sound does Splat come from? The character?

John:

Splat comes from many different parts. Now, we did some of the footsteps... Let's see, I guess you could say Splat, Foley-wise would come from a bit of a wet shammy, but that's a very small part of what Splat was.

Meryn:

The noises that come from Splat might be my favorite in that film because it's adorable. So everyone should go watch it. We can’t thank you enough for talking to us John!

John:

Well, I wish everybody a wonderful day.

John:

Yeah, absolutely. This was a great way to have a Thursday. Can’t wait to see you in July!